Should I exercise with pain?

Should I exercise with pain? A common question we hear in the clinic, the gym and on sporting fields so let’s look into exercising with pain.

It’s always important to listen to your body and to understand the difference between a general ache versus pain, particularly with exercise.

But what do you listen for?

The first and most important point to note is that pain is the body’s normal response to perceived danger.

It’s like having an alarm system that will go off if something nasty is detected. So while pain is a normal body reaction, it’s not when it lasts longer than 48 hours after exercise, or when that same pain somewhere in your body starts to hurt during the day, even when not exercising.

How much is too much

You need to be honest and self-evaluate both during and after exercise.

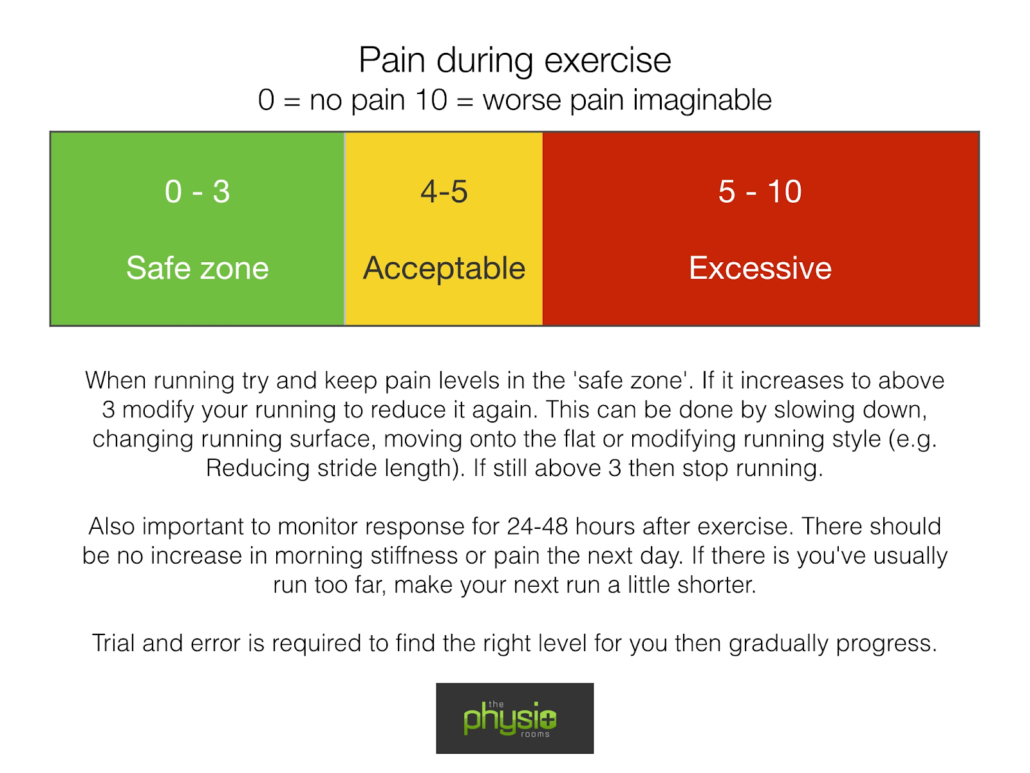

You can easily do this by giving your pain a rating out of 10; the higher the number, the greater the pain. The following key will then help guide your response:

Am I safe to move?

Usually we ask a medical professional (Doctor or Physiotherapist) for a diagnosis, medications or advice about the best treatment.

What you want to know from them is whether you have a condition that means you should avoid exercise and movement at the moment. There are really very few of these thankfully. In fact, for most muscle, joint and nerve pains, exercise done correctly is not only safe but strongly recommended. This includes joint pain like hip and knee arthritis, and neck and back pain, including spondylosis, sciatica and disc problems.

Understand that “Hurt doesn’t = Harm”

For most of our lives, pain is a useful thing that protects our body.

If I touch a hot stove, I feel pain and I quickly withdraw my hand. Pain is like an alarm that warns me of danger.

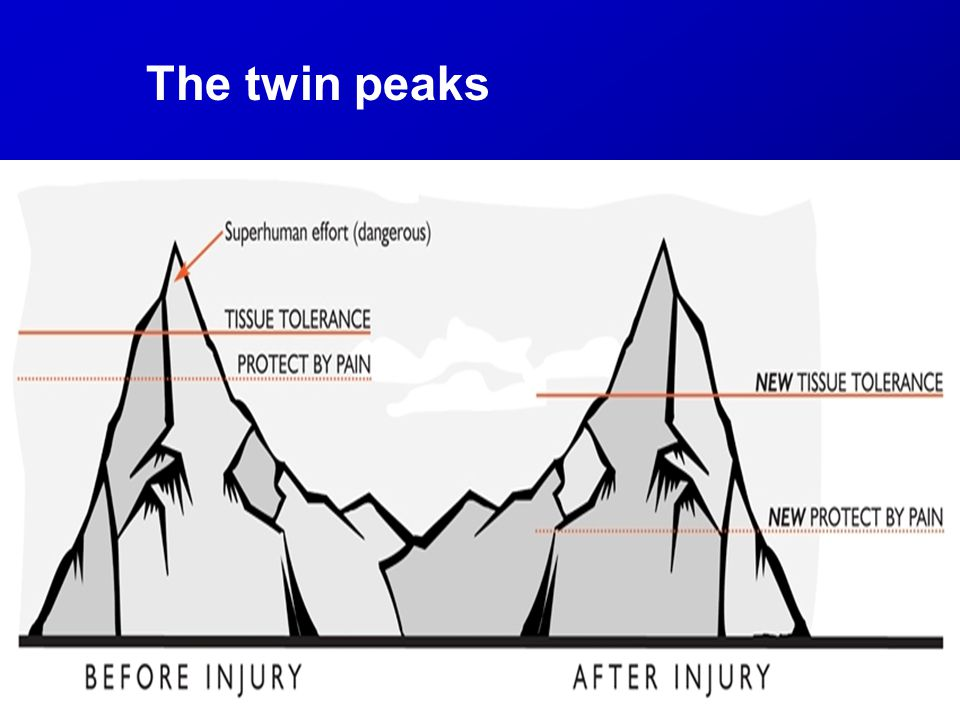

Unfortunately, persistent pain is much less useful.

It is almost always well out of proportion to any damage going on in the body, and people can feel terrible pain when moving even when it is not dangerous. The alarm that is usually so useful becomes “over-protective”.

This means that if there is a particular movement you do that causes you pain, and has done for some time, it is very likely that that pain is not indicating you are doing any harm. You are sore, but safe. This is important to understand because otherwise exercise makes no sense and you will just be miserable!

Another way to think of this is like a lowering of the pain threshold. A certain part of the body, or many parts of the body, becomes over-sensitive to movement and feels more painful than it needs to be.

Will exercise help my pain?

Most people find their pain decreases with movement and exercise when they find the right thing for them, at the right ‘dose’ and once they manage to get a few weeks of it under their belt. This is not guaranteed though, it depends on a lot of factors, so remember advice and progression from a qualified Health Professional is recommended.

Get into the swing of it

When you have decided what you want to do, decide when you want to do it.

Aim for 3-4 times per week. More than that is okay if the exercise is quite easy. But if you are working hard it is often best to give your body a day off in between workouts so it has time to recover and adapt.

When you know what you want to do and when you want to do it, do it!

And for now, don’t worry about anything more than doing it. The key is to “just show up”, at the gym or in the park. Explore the movements involved in whatever you are doing. Get used to how your body feels, see how it reacts and see how your pain reacts. Enjoy moving your body again. Don’t feel you have to work yourself to exhaustion.

If you miss a workout, don’t beat yourself up. There is no value to doing this. Just try again next time

What about the pain?

The golden rule of exercise and pain is to “exercise within tolerable pain that plateaus during exercise and does not continue to rise significantly, and gradually decreases once you have finished”.

We know that pain is like an “over-sensitive alarm” and doesn’t mean you are doing damage, therefore you don’t need to avoid pain. Some pain or discomfort might be necessary to get a good workout. But, of course, you don’t want too much pain, especially if it is the kind of pain that ‘flares up’ after exercise and stops you from working and sleeping properly.

Tolerable pain is hard to quantify as it is very subjective and can be perceived differently for each person.

For some it will be mild discomfort, for others it will be more. Another way of thinking of tolerable pain is something you can cope with and feel is manageable. It should not feel frightening and you should still feel in control.

It will take some trial and error to find this level. At first, you might do too much and flare up your pain. Take time to let it ease off then try again, doing a little less. Think of a flare up as a learning process, as then you will know what is “too much” for you. As you continue to exercise, it is likely that what was once too much will become achievable.

Be ready for DOMS!

Everyone, regardless of whether they have a painful condition, is likely to feel sore the next day or two after trying something new.

This is called DOMS or Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness. So, if you do feel worse after your first session or two, consider that this might not be a flare-up of ‘your’ pain but normal muscle soreness that will diminish over time.

Time to push-on

Each time you push out of your comfort zone, your body adapts and gets stronger for next time.

Once you have had a few weeks in a row of “showing up” and doing exercises such as STRONGCorps, no matter how little, and you have worked out your level of tolerable pain, it is time to start pushing on to get the most benefit from your time and effort that you can.

Once you are in the habit of exercise, you might find that you end up doing the same thing each time. For example, walking the same route or lifting the same weights. Unfortunately, the body quickly adapts to this and you will stop getting as much benefit. You are just maintaining things, but not getting any fitter or stronger. To get the most from exercise, you have to keep moving out of your comfort zone, a little bit at a time, with variety being the spice of life!

Over time, the benefit adds up. To make sure you are doing this, it helps to keep track of what you are doing. You can make sure you progress over time. For example, try to walk a bit further, or do the same distance in a shorter time. If you are doing home exercise or weights at the gym, try to do a few more “repetitions” or lift heavier weights.

What doesn’t challenge you, won’t change you!

As you start to build the exercise habit, this becomes key.

The best exercise is one that you enjoy, because you will stick to it. This is true, but it is also true that part of your exercise should be quite hard. Not all of it, but maybe just the last few minutes or the last couple of repetitions. Give yourself some tough love. Are you out of breath? Sweating? Are your muscles tired? If not, you may not be getting the benefit you want.

Another benefit of keeping track of what you are doing is that it helps you to follow your exercise programme based on what you plan to do that day, rather than based on your pain. Allowing your pain to ‘dictate’ what you do often leads back into the spiral of doing less and less.

Key points to remember

- Get advice from an experienced physiotherapist to determine what the injury is and ensure it’s safe to continue exercising.

- Modify training to bring it to a level that doesn’t aggravate symptoms during or after exercise.

- Calm the pain with ice, heat, massage, taping or whatever works for you.

- Identify the cause of the problem (training error, muscle weakness etc.) and address it.

- Rehab with strength and conditioning work from your physio and make sure you do it!

- Develop some strategies to reduce pain when exercising as mentioned above and practice these in training to see what works.

- Taper well before a race or event, as generally less is more when managing an injury, give it some time to settle before and after race day.

- And finally, plan long term, not just for the next race. Discuss with your physio how you can fully rehab the issue. This might mean a reduction in training volume and gradual build up when races have finished.

Craig Gregory is an APA Sports Physiotherapist Practice Principal at Balmain Sports Medicine. He holds a Masters Sports Physiotherapy, Bachelor of Applied Science (Physiotherapy) and Level 1, 2 & 3 APA Sports Physiotherapy. Craig can be contacted via email craig@balmainsportsmed.com.au.

© V&B Athletic

© V&B Athletic © V&B Athletic

© V&B Athletic © Pace Athletic

© Pace Athletic

© V&B Athletic

© V&B Athletic